A not at all brief history of tinned fish

Napoleon’s rise, a confectioner-turned-inventor and the Religion of Gastronomy

From the wind-whipped shores of Portugal’s Alentejo coastline to subversive Insta food blogs, the humble sardine has long carried outsize cultural cachet as a vessel for visual storytelling and clever marketing.

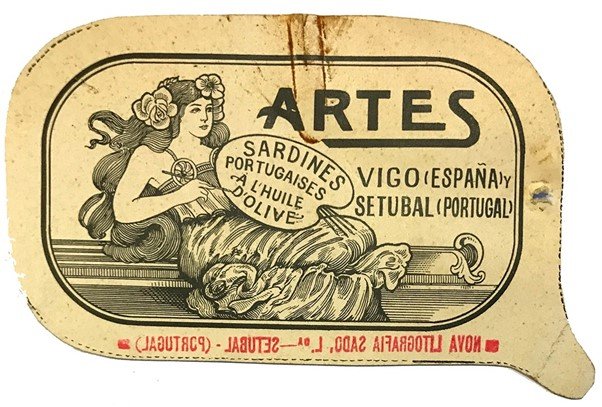

For the better part of two centuries, exquisite tin designs have transformed ordinary canned fish into miniature canvases, elevating preserved seafood from simple sustenance to complex depictions of European maritime life and history. Ornate labels spin narratives, vibrant hues seduce consumers, selling an idealised version of the effortlessly leisurely European sardine-centric lifestyle.

Beyond just identifying the tins’ contents, the packaging whisked (and still whisks today) shoppers away to reveries of hardy fishermen hauling in glistening catches, tranquil harbours shimmering at sunset, and mythical mermaids enticing fish up from sapphiric depths. As we’ll learn, the dedication to creating enticing packaging plays a massive role in the popularity of tinned fish today.

But this artistic legacy was only made possible by the invention, and proliferation, of canned fish. Which is, in part, down to a guy called Nicolas Appert. And Napoleon. But we’ll get to that.

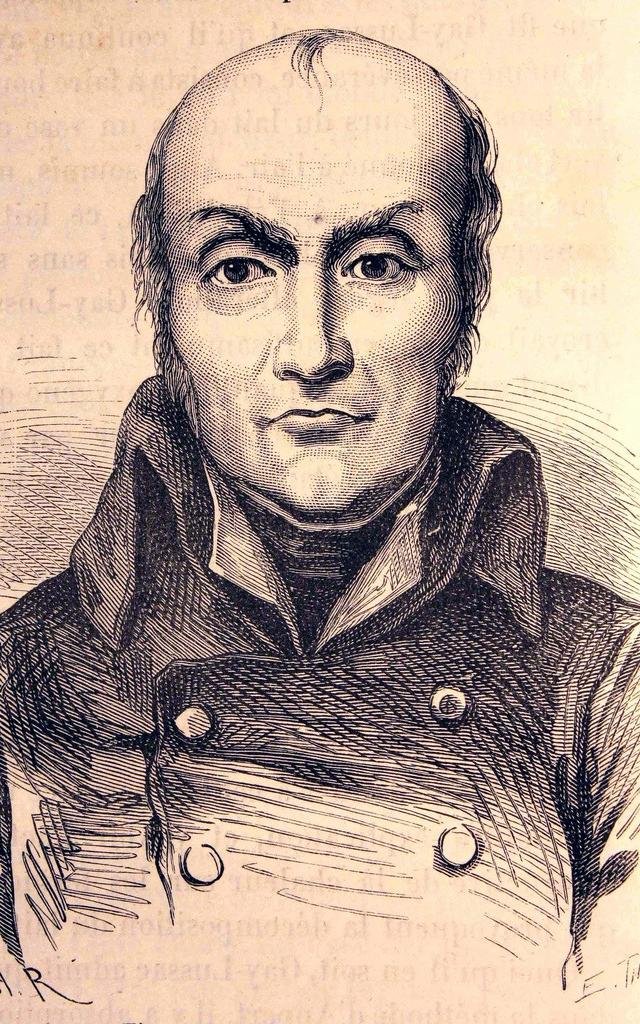

Nicolas Appert, the father of food science

Known as the “father of food science”, Nicolas Appert’s pioneering preservation techniques for removing air, heat processing, and hermetically sealing foods into jars paved the way for modern canning. His method has been improved somewhat since he invented it around 1800, but the gist is the same as it was back in his day. Maybe, if Appert could’ve foreseen the longevity of his achievement, he would’ve done some things differently. Because his road to success was anything but straight.

This is Nicolas Appert. I think he looks like a pretty harsh guy, just judging on the severity of those brows and the tightness of that mouth. But maybe I’m projecting.

Ninth of eleven children, Appert grew up in the 20-bedroom hostelry his family ran in Chalons-en-Champagne, without a scratch of formal education to speak of.

He worked at the family boozer throughout his adolescence, learning from his father the rudiments of pickling and brewing, but apparently, as you’ll see here, neglecting to learn how to run a business.

When he turned 20, he and one of his many brothers decided to strike out and open their own brewery. The biography I read (linked below - it’s where most of this article’s Appert intel comes from) didn’t have much to say about this fraternal venture, but from his almost immediate pivot into service as a head cook in the palace of German nobleman Prince Palatin Duc de Deux Ponts, we can safely assume it didn’t go all that well.

He cooked for the prince for about 13 years, and then, when he was 34, he pivoted again and started manufacturing sweets in Paris. He was, by all accounts, a pretty solid pâtissier, but his career was disrupted by the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789. The revolution derailed his enterprising efforts before he had the chance to derail them himself, as he played such an active role that he even assisted in the execution of King Louis XVI. His actual role is unclear, but I like to think he offered the unlucky king a final pre-guillotine pastry to settle his stomach.

Appert’s leal service to the revolutionary forces didn’t protect him from their scrutiny, though. By 1793, during what’s affectionately known as the Reign of Terror, the revolution was at the height of its brutality. Poor Appert was considered by those in charge to be altogether too moderate, which they found super suspicious. He was interrogated, searched, arrested, imprisoned, narrowly avoided a trip to the guillotine and was, eventually, released in 1794 when the violent revolutionary government was overthrown and replaced by the Directory, led by a young Napoleon Bonaparte.

The following year, Napoleon was busy working as the commander of the Army of the Interior. Napoleon is often attributed with coming up with the oft quoted adage that “an army marches on its stomach”, which is why, in 1795, he set up a prize fund of 12,000 francs - to be awarded to the man who invented a new way of preserving nutritious food for his Grand Armée to scoff on the road to imperialistic success.

This was a stroke of fortune for Appert who, alongside his string of dismal business ventures, had long been tinkering with new methods of food preservation.

Keepin’ meats eatable

Pre-Appert, there were a number of ways people increased the shelf life of fresh food. If you hailed from somewhere cold, you could freeze it using ice. If you lived somewhere toasty warm you could dry it out in the sun. Alternatively, you could salt it and immerse it in fat confit-style, cure it using either smoke or salt, pickle it using a vinegar, or suspend it in a sugary preservative like honey.

Appert, though, wanted to find a way to preserve food that didn’t drastically alter its flavour, or transform it into teeth-shattering hard tack. He thought that you could maintain the gastronomic integrity of any victuals if only there were a way to stop the food from spoiling. The problem was that Appert hadn’t the foggiest idea why food spoiled in the first place. After all, it’d be another sixty-odd years until Louis Pasteur would reveal the existence of microorganisms. All Appert had was a hunch.

His hunch told him that it was the air that was somehow kickstarting decay. So, all his theories worked around finding ways of cooking foods and then, without relocating the food from the cooking vessel, remove as much excess air as possible and seal the food tightly inside.

He started out using specially blown glass bottles with cork stoppers. This was a viable method - proven by accounts of sailors taste testing Appert’s preserved produce as early as 1803 (i.e. ages before other people started canning stuff). Here’s what they had to say:

“The meat broth is really good... the boiled meat is eatable, yellow peas and garden peas possess the freshness and the flavour of recently harvested vegetables.”

Deliciously eatable meat and peas! What more could a starving, scurvy-riddled sailor want?

The glass bottles he was using were a bit heavy and fragile, but the method worked. Which should have been a turning point for Appert. But, in spite of his success, it would take until 1809 for Appert to receive any formal recognition of his achievements from Napoleon or his cronies in charge.

When he did finally get his just desserts, Appert was given two options. Option one was to claim the patent to his invention, which would’ve enabled him to profit from the worldwide usage of his technique. Option two was to relinquish his patent in return for Napoleon’s 12,000 franc prize pot. For context, ChatGPT reckons that 12,000 francs would be worth about £1,575,484 today. A pretty hefty chunk o’ change.

We’ve already established that Appert does not make great business decisions. So, predictably, he took the prize money and scarpered. He sank all 12,000 francs pretty quickly, and, although lots of clever people around the world genuinely appreciated his work - awarding him medals, prizes, accolades and applaudatory news articles (and, since his death, naming university buildings and loads of Parisian streets after him) they never really gave him much more money. He roved around France for a while, starting new businesses and promptly running them into the ground, getting evicted from various premises, and, eventually, at the fairly grand age of 91, he suffered a lonely death and ended up buried in a pauper’s grave. Sad times.

Let’s circle back round to the history of tinned fish

Anyway, Appert’s revolutionary methods directly sparked the rapid Europe-wide rise of preserved fish throughout the 1800s. The French led the way, with canneries exploding across the Breton coastline through the first half of the 19th century. But rampant overfishing led to a series of French sardine crises, which forced businesses to relocate from France to further down the coastline.

Seeking fishier waters, many of these businesses ended up in Portugal. Towns like Setúbal acted as a Franco-Portuguese industrial hub. The canning communities that sprang up there have played a major role in the country’s economy ever since, and dictated culinary traditions that still persist today.

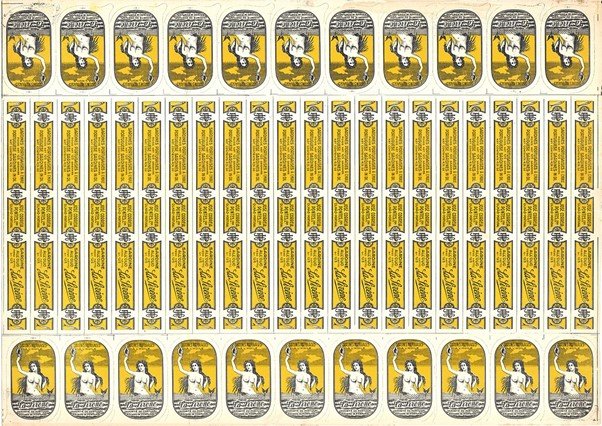

By the early 20th century, the number of canneries across Portugal rose to around 400. Iconic illustrators like Raul de Caldevilla were hired as visual mythmakers, tasked with creating whimsical designs that anthropomorphised the humble sardine into a storybook character adrift in a lovingly-rendered nautical fantasy. The tins, or their paper labels, were no longer just there to declare a brand name and detail what was hiding inside - they were now a device that helped lure consumers in.

So the tins started trading in plain covers for rich decoration. Going from functional…

(there aren’t loads of examples of tins from this era, obviously, but they would’ve been more like this one, found on a Spanish Civil War battlefield in Guadalajara)

…to downright fabulous.

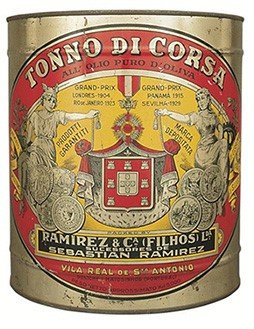

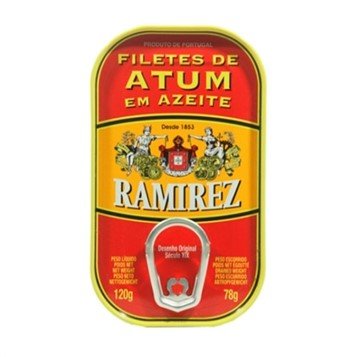

This is one of the tins used by Ramirez - a cannery that was opened in 1853 and is still going strong today. It was kept in the family at least until the death of the founder’s great-grandson in 2022 (I’m struggling to find who’s in charge now though). Here’s the same product, available to buy online with a design that essentially hasn’t changed since the brand’s inception.

Just like the ups and downs of Appert’s business ventures, the prettification of sardine packaging doesn’t progress in a straight line. The industry’s 20th century wartime boom put a bit of a pin in dandy design, for one.

Until I started writing this piece, I hadn’t realised that Portugal actually maintained neutrality during both world wars, supplying, amongst other things, canned fish to both sides of each war. Sardines are cheap, practical, plentiful and packed with protein, which makes them the perfect low-cost people fuel for civilians and soldiers alike. The wartime period marked the loftiest heights the industry would reach across the entire history of tinned fish, and it’s been in a fairly steady regression ever since.

The declining appetite for canned fish, plus the added efficiency of increasingly automated systems, means that many of the canneries that were active in the first half of the 20th century have since closed down or been replaced. But there are still some brands keeping the hand-cooked, gorgeously-designed traditions of this industry alive and well. A fact that Oscar Wilde’s somewhat unexpected son, Vyvyan Holland, would be absolutely thrilled about, as he was apparently* the founder of the world’s first sardine tasting club.

“In the larders of some European gourmets, tins of sardines in olive oil occupy a place of honor alongside pots of foie gras with truffles or jars of caviar. A cult has built up around these canned fish, which, with its preaching of the special qualities of the best brands, the correct year and maturity period within the tin, constitute a kind of gastronomical religion”

Gastronomy might just be the first religion I feel like I can fully get behind. And the glorious packaging would be a big part of my worship.

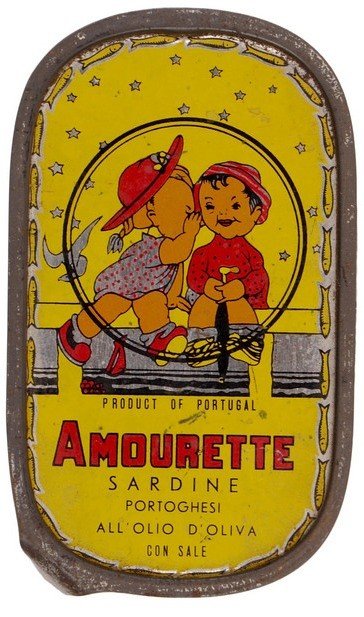

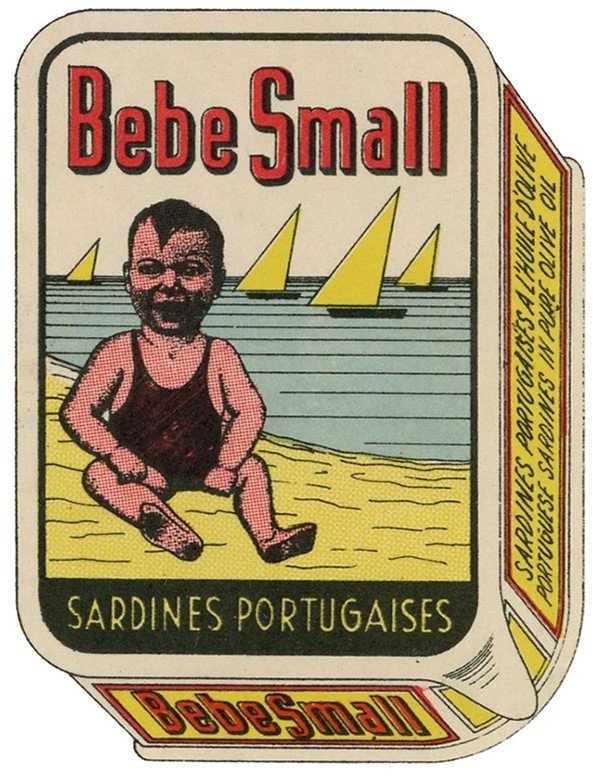

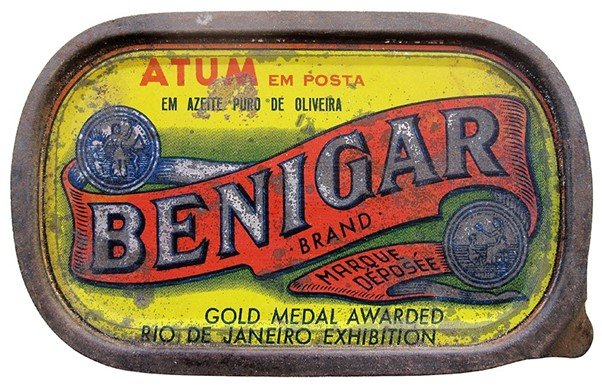

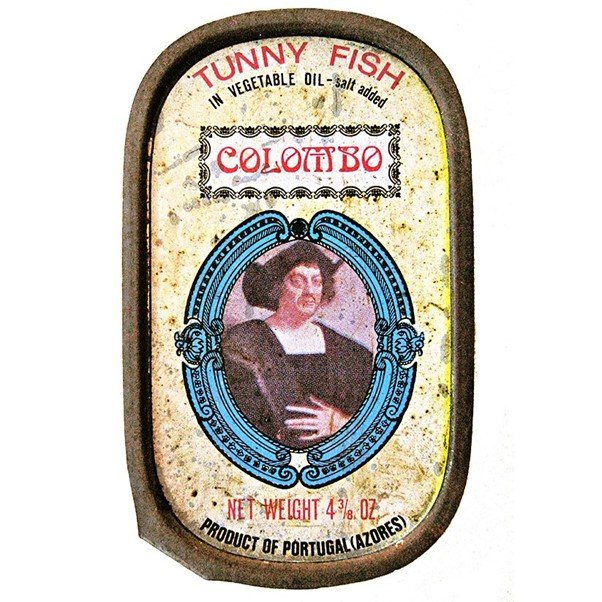

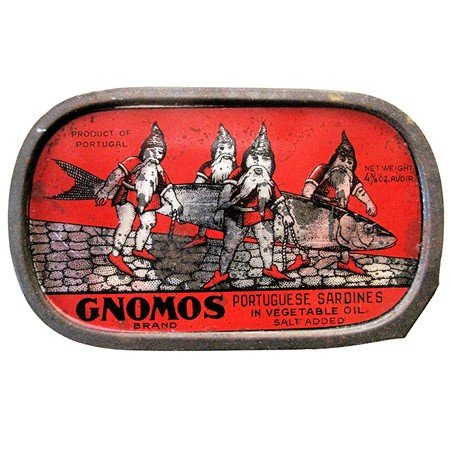

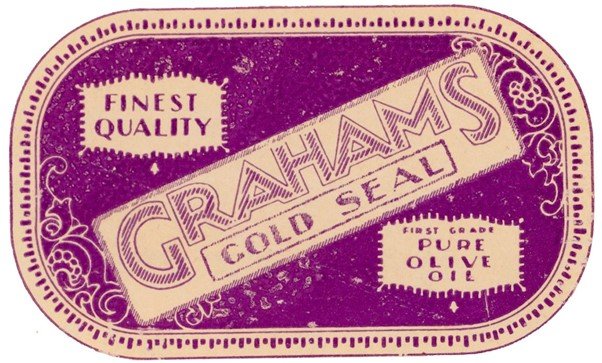

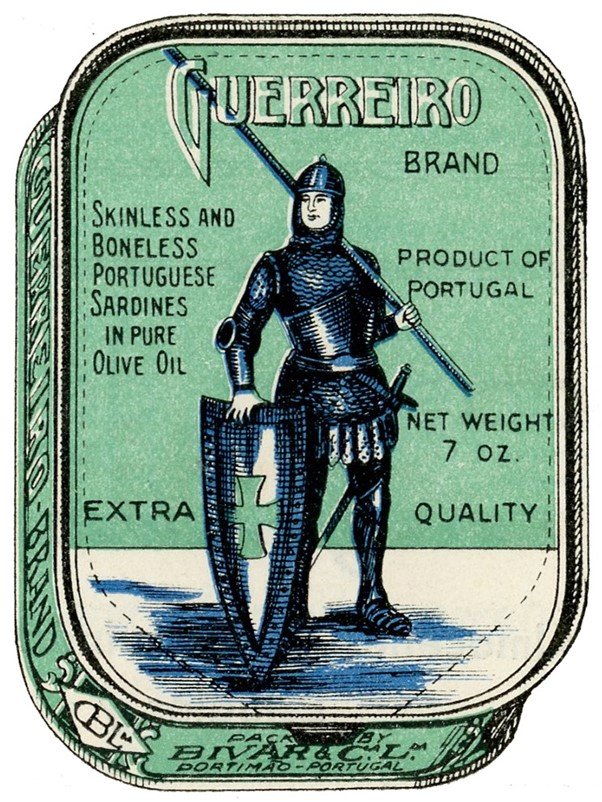

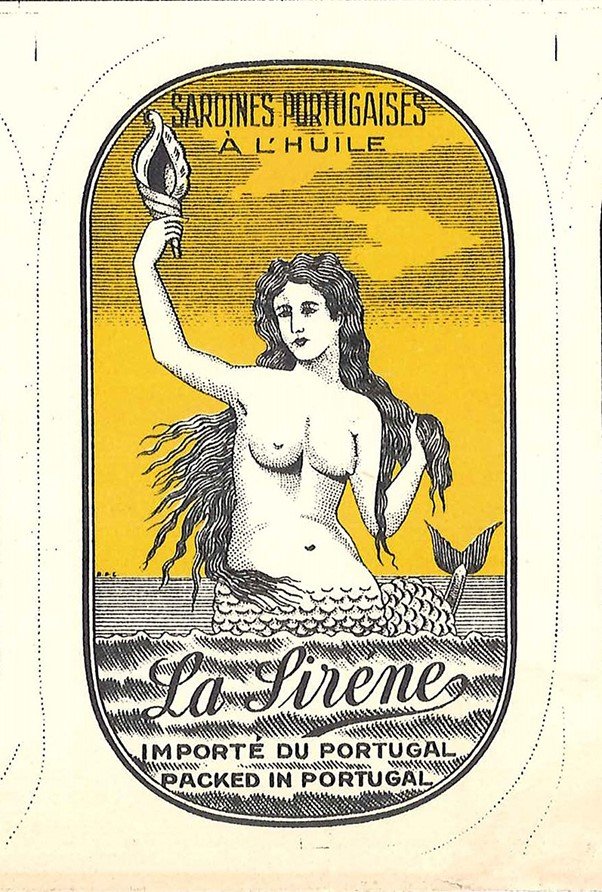

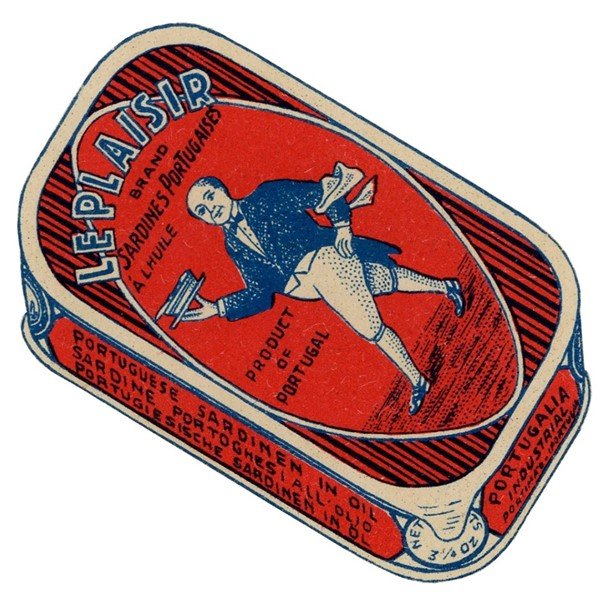

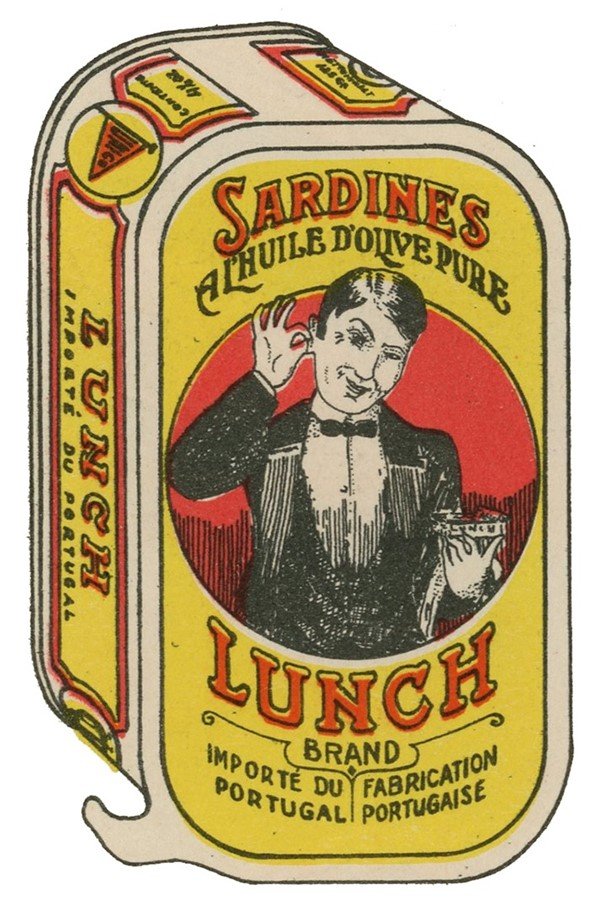

The artwork itself

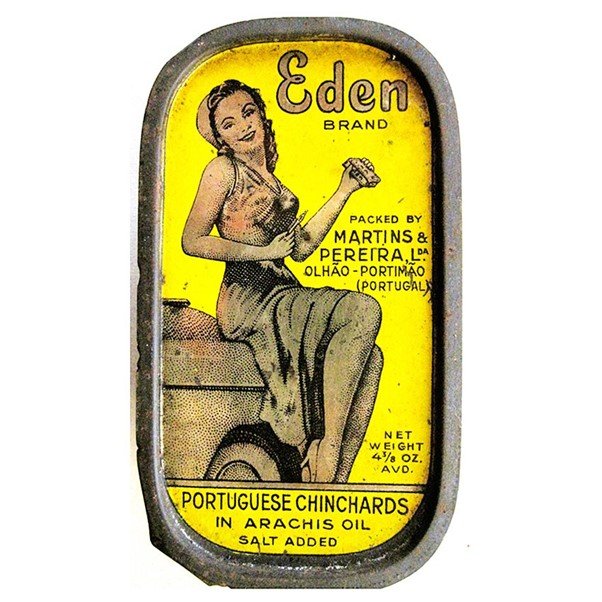

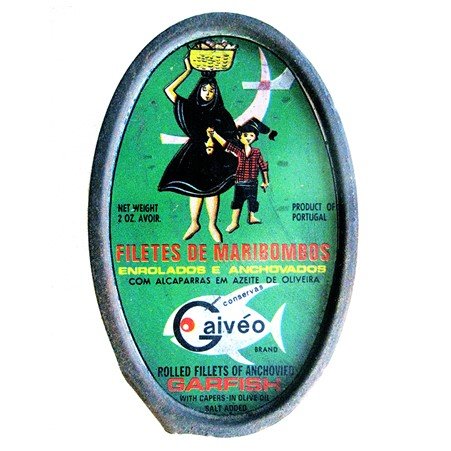

The tins’ artwork called to 20th century consumers, and, spoiler alert, it still calls to consumers in the present day. As I said in the intro, it romanticises the idea of life at sea and paints a picture of tranquil harbourside life. There are lots of mythical beings involved - mermaids, Greco-Roman goddesses, old-world knights and timeless, ageless femininity. The attention to detail and colourful opulence add a touch of glamour to this inherently working class existence.

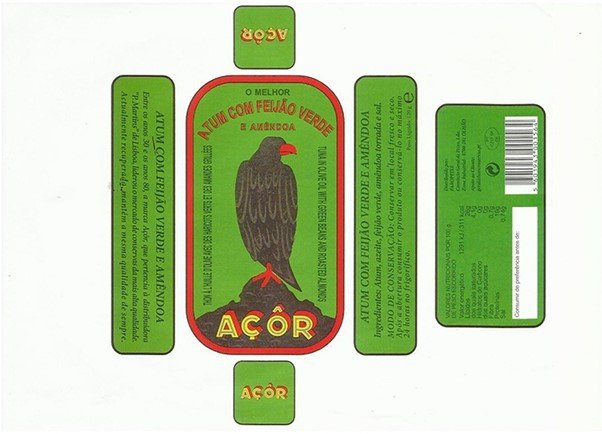

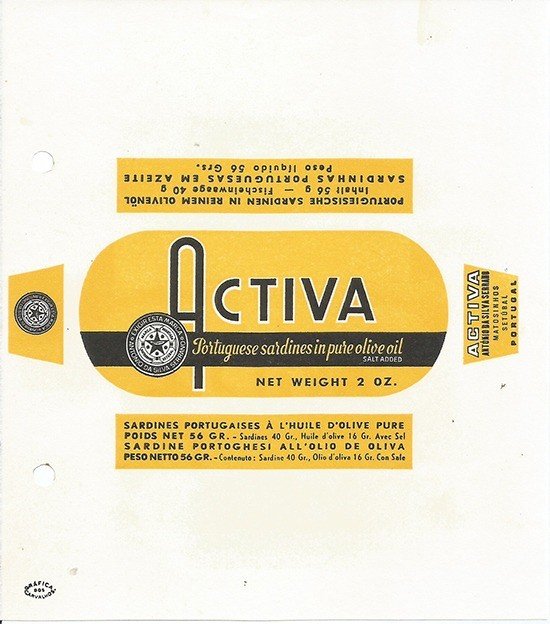

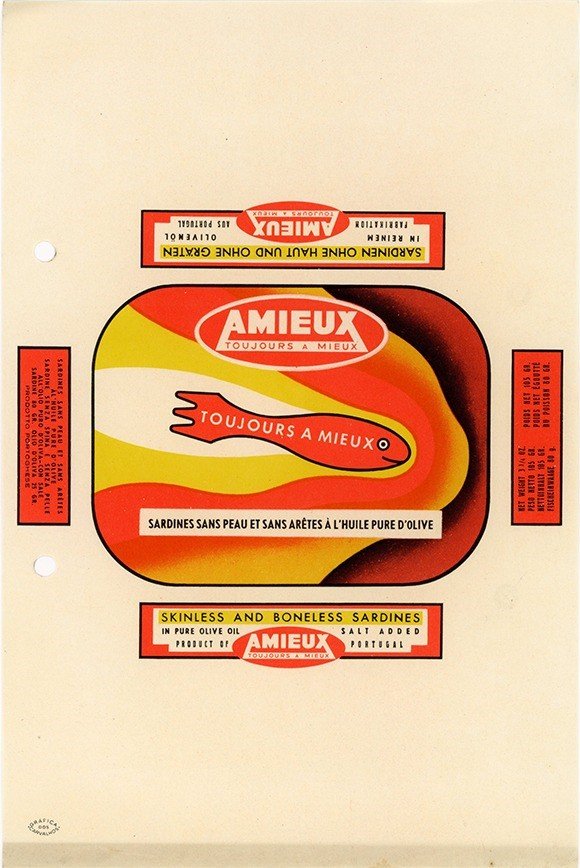

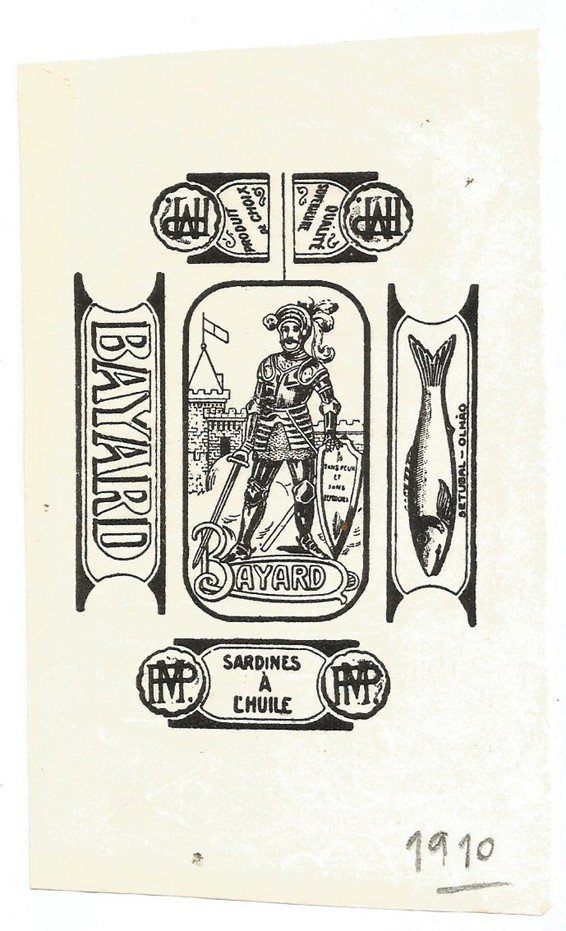

The illustrators and designers were hired to construct mythical worlds around the products through fantastical imagery and catchy slogans (one of my favourites was simply donnez-moi la sardines, which translates roughly to “gimme dem sardines”). Here’s a carousel showing some of my faves, from the Conservas de Portugal archive.

Conservas de Portugal is a digital museum, entirely built around the preservation and celebration of the Portuguese canning industry. You can browse through the collection online, or, if you happen to be in Lisboa any time soon, you can visit their partner project CAN THE CAN for a real-life taste of traditional tinned fish and a flavour of what the history of tinned fish really means.

Although the fish were caught, prepared and canned locally in Portuguese ports, the industry’s French roots means that the can art is, and always has been, heavily Francophilic. The Nouveau and Deco influences are particularly striking - like in these examples:

The visually complex designs elevate the humble canned sardine from kitchen staple to objects d’art. Art Nouveau’s ornamental design style embraces flowing, naturalistic forms inspired by the intricacies of plants and flowers, and you can spot an homage to that here in the whiplash curves, nature motifs like swirling waves and undulating fishy bodies, and intricate linework.

Some tins choose to channel Art Deco’s bold geometric shapes, with rich colours and the kind of streamlined aesthetics that rose to popularity in the 1920s and 30s. The elongated figures, angular fonts and geometric designs radiating from illustrated mermaids all exemplify the era’s fascination with futurism and modernity. When this is blended with the industry’s folky heritage, you effectively encode cultural narratives into the functional packaging.

(None of this is to say that style has stayed static since the mid-1800s. In the mid-20th century, the Conservas archive shows a shift to designs that replace the romanticism of earlier designs with more utilitarian low-res photographic still-lifes of the actual can contents. I think I speak for us all when I say, respectfully, ew. But let’s ignore these ugly little interlopers. Because I hate them. And this is my article, so I can do what I like.)

The tinned fish renaissance

Now, even more exciting than casting ourselves back into the briny past, I’m thrilled to be here for a new era. A tinned fish renaissance, if you will, where brands like Scout, Fishwife, Siesta, Jose Gourmet, Conservas de Cambados, CAN THE CAN, TinCanFish and The Tinned Fish Market are shining the spotlight back onto the majesty of tinned fish. And they’re keeping the tradition of spinning tales on miniature metallic canvases alive and well.

The modern maximalism in Fishwife’s designs, built around bold colours and vintage everything sells well. Their quirky hand-drawn logo and retro-inspired colour palette exude a sense of old-world Euro-centric craftsmanship and idyllic coastal living.

Long gone (at the up-market end of the sardine scale, anyway) are the oversaturated mid-80s photographs of the tins’ contents. That’s not really what these renaissance consumers care about. Now, we’ve returned full force to the sustainable, slow-food narrative of a seemingly humble but deliciously luxurious Mediterranean lifestyle.

And audiences are feeling that story keenly. Especially city-slicked or seaside-starved American Gen Z’ers, whose urbanite lives are so dominated by fast everything that the very idea of a dolce far niente afternoon of terrace-bound relaxation, peppered with the consumption of tapas-style tinned food repasts and perfectly chilled wine, is at once fantastical and impossibly tempting.

As one critic observed, the visuals used across modern tin design taps into contemporary “Europecore” trends by embodying the effortless minimalism of simple, humble but elevated living. For more on that phenomenon, also see 2023’s Tomato Girl Summer and European Stealth Wealth trends. These oily little critters are being reinvented by the social media generation as “hot girl snacks”

““It’s always pickle girlies this, olive girlies that. What about the tinned fish girlies? The vibe, the lifestyle, the taste level, the glowing skin is unmatched.””

Sardinecore

Young people in particular are seeking attainable luxury. Peeling open a gorgeously designed tin of gourmet snacks, even when the rest of your young life is chaotic and economically uncertain, gives a little thrill of sumptuousness, and scratches the itch for indulgence so many of us are unable to otherwise assuage.

Today’s tinned fish purveyors have updated the romantic aesthetic in keeping with more contemporary tastes, whilst simultaneously keeping alive one of the longest-running storytelling traditions in food commerce and consumer design. The miniature canvases decorating our Insta-worthy tinned gourmet snacks still spin tales of European vacations, handcrafted delicacies and nostalgic coastal grandeur, can by charismatic can. Which is wonderful.

And this trend isn’t just for normie food influencers on socials. Upmarket designers are trying to jump on the Sardinecore trend too - check out this £28,800 sardine-themed handbag from Bottega Veneta

Or this £900 sardine tin wall art

To me, though, both of these examples (and there are loads more out there from brands that have jumped on the bandwagon) feel like uncouth attempts by the ultra-rich to ingratiate themselves into a cultural movement that they are inherently apart from. Because this is a movement rooted in simplicity. In savouring something inexpensive but nonetheless rewardingly tasty. In elevating a traditionally working-class repast without splurging unnecessary bags of cash on it.

If you’re the sort of person who has thirty grand lying around, feel free to splurge on a handbag and an overpriced flavour-of-the-moment piece of art, then go right ahead. But know that none of these bougie Sardinecore trinkets could ever really beat a perfectly prepared sardine, lovingly evicted from its artfully designed can and smeared across a really (really) good piece of toast.

*I say apparently because this “fact” pops up all over the place but nobody seems to have verified it enough for me to be confident.

Also, here’s the Nicolas Appert biography, if you’re interested: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240546659_Nicolas_Appert_Inventor_and_Manufacturer